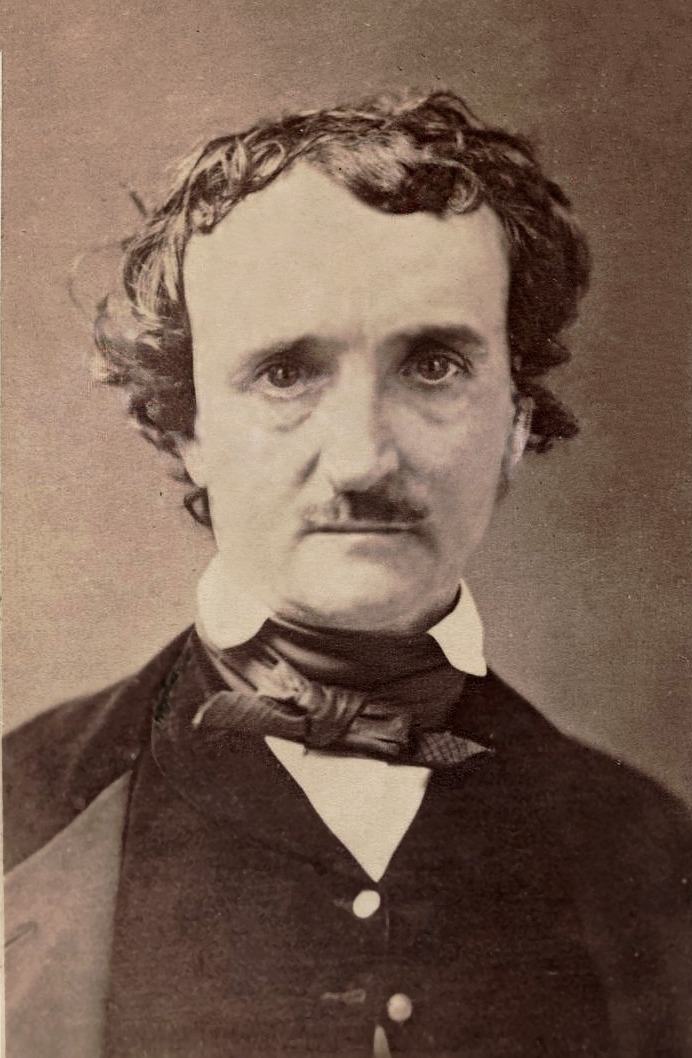

Edgar Allan Poe (1809 � 1849) was an American writer, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is widely regarded as a central figure of Romanticism in the United States and American literature as a whole, and he was one of the country's earliest practitioners of the short story. Poe is generally considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre and is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction.

He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career.

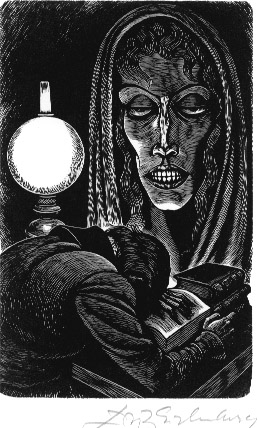

BERENICE

Misery is manifold. The wretchedness of earth is multiform. Overreaching the wide horizon like the rainbow, its hues are as various as the hues of that arch, as distinct too, yet as intimately blended. Overreaching the wide horizon like the rainbow! How is it that from Beauty I have derived a type of unloveliness ? from the covenant of Peace a simile of sorrow ? But thus is it. And as, in ethics, Evil is a consequence of Good, so, in fact, out of Joy is sorrow born. Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of today, or the agonies which are, have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been. I have a tale to tell in its own essence rife with horror I would suppress it were it not a record more of feelings than of facts.

My baptismal name is Eg�us that of my family I will not mention. Yet there are no towers in the land more time-honored than my gloomy, grey, hereditary halls. Our line has been called a race of visionaries: and in many striking particulars in the character of the family mansion, in the frescos of the chief saloon, in the tapestries of the dormitories, in the chiseling of some buttresses in the armory, but more especially in the gallery of antique paintings, in the fashion of the library chamber and, lastly, in the very peculiar nature of the library's contents, there is more than sufficient evidence to warrant the belief.

The recollections of my earliest years are connected with that chamber, and with its volumes of which latter I will say no more. Here died my mother. Herein was I born. But it is mere idleness to say that I had not lived before that the soul has no previous existence. You deny it. Let us not argue the matter. Convinced myself I seek not to convince. There is, however, a remembrance of �rial forms of spiritual and meaning eyes of sounds musical yet sad a remembrance which will not be excluded: a memory like a shadow, vague, variable, indefinite, unsteady and like a shadow too, in the impossibility of my getting rid of it, while the sunlight of my reason shall exist.

In that chamber was I born. Thus awaking, as it were, from the long night of what seemed, but was not, nonentity at once into the very regions of fairy land into a palace of imagination into the wild dominions of monastic thought and erudition it is not singular that I gazed around me with a startled and ardent eye that I loitered away my boyhood in books, and dissipated my youth in reverie but it is singular that as years rolled away, and the noon of manhood found me still in the mansion of my fathers it is wonderful what stagnation there fell upon the springs of my life wonderful how total an inversion took place in the character of my common thoughts. The realities of the world affected me as visions, and as visions only, while the wild ideas of the land of dreams became, in turn, not the material of my everyday existence, but in very deed that existence utterly and solely in itself.

* * *

Berenice and I were cousins, and we grew up together in my paternal halls, yet differently we grew. I ill of health and buried in gloom she agile, graceful, and overflowing with energy. Hers the ramble on the hill side, mine the studies of the cloister. I living within my own heart, and addicted body and soul to the most intense and painful meditation she roaming carelessly through life with no thought of the shadows in her path, or the silent flight of the raven-winged hours. Berenice ! I call upon her name Berenice ! and from the grey ruins of memory a thousand tumultuous recollections are startled at the sound! Ah! vividly is her image before me now, as in the early days of her light-heartedness and joy ! Oh ! gorgeous yet fantastic beauty ! Oh ! Sylph amid the shrubberies of Arnheim ! Oh ! Naiad among her fountains ! and then...then all is mystery and terror, and a tale which should not be told. Disease, a fatal disease fell like the Simoom upon her frame, and, even while I gazed upon her, the spirit of change swept over her, pervading her mind, her habits, and her character, and, in a manner the most subtle and terrible, disturbing even the very identity of her person! Alas! the destroyer came and went, and the victim where was she? I knew her not or knew her no longer as Berenice.

Among the numerous train of maladies, superinduced by that fatal and primary one which effected a revolution of so horrible a kind in the moral and physical being of my cousin, may be mentioned as the most distressing and obstinate in its nature, a species of epilepsy not unfrequently terminating in trance itself trance very nearly resembling positive dissolution, and from which her manner of recovery was, in most instances, startingly abrupt. In the meantime my own disease for I have been told that I should call it by no other appellation my own disease, then, grew rapidly upon me, and, aggravated in its symptoms by the immoderate use of opium, assumed finally a monomaniac character of a novel and extraordinary form hourly and momentarily gaining vigor and at length obtaining over me the most singular and incomprehensible ascendancy. This monomania, if I must so term it, consisted in a morbid irritability of the nerves immediately affecting those properties of the mind, in metaphysical science termed the attentive. It is more than probable that I am not understood but I fear that it is indeed in no manner possible to convey to the mind of the merely general reader, an adequate idea of that nervous intensity of interest with which, in my case, the powers of meditation (not to speak technically) busied, and, as it were, buried themselves in the contemplation of even the most common objects of the universe.

To muse for long unwearied hours with my attention rivetted to some frivolous device upon the margin, or in the typography of a book to become absorbed for the better part of a summer's day in a quaint shadow falling aslant upon the tapestry, or upon the floor to lose myself for an entire night in watching the steady flame of a lamp, or the embers of a fire to dream away whole days over the perfume of a flower to repeat monotonously some common word, until the sound, by dint of frequent repetition, ceased to convey any idea whatever to the mind to lose all sense of motion or physical existence in a state of absolute bodily quiescence long and obstinately persevered in such were a few of the most common and least pernicious vagaries induced by a condition of the mental faculties, not, indeed, altogether unparalleled, but certainly bidding defiance to any thing like analysis or explanation.

Yet let me not be misapprehended. The undue, intense, and morbid attention thus excited by objects in their own nature frivolous, must not be confounded in character with that ruminating propensity common to all mankind, and more especially indulged in by persons of ardent imagination. By no means. It was not even, as might be at first supposed, an extreme condition, or exaggeration of such propensity, but primarily and essentially distinct and different. In the one instance the dreamer, or enthusiast, being interested by an object usually not frivolous, imperceptibly loses sight of this object in a wilderness of deductions and suggestions issuing therefrom, until, at the conclusion of a day-dream often replete with luxury, he finds the incitamentum or first cause of his musings utterly vanished and forgotten. In my case the primary object was invariably frivolous, although assuming, through the medium of my distempered vision, a refracted and unreal importance. Few deductions, if any�were made; and those few pertinaciously returning in, so to speak, upon the original object as a centre. The meditations were never pleasurable; and, at the termination of the reverie, the first cause, so far from being out of sight, had attained that supernaturally exaggerated interest which was the prevailing feature of the disease. In a word, the powers of mind more particularly exercised were, with me, as I have said before, the attentive, and are, with the day-dreamer, the speculative.

My books, at this epoch, if they did not actually serve to irritate the disorder, partook, it will be perceived, largely, in their imaginative, and inconsequential nature, of the characteristic qualities of the disorder itself. I well remember, among others, the treatise of the noble Italian Coelius Secundus Curio "de amplitudine beati regni Dei" - St. Austin's great work the "City of God" and Tertullian "de Carne Christi," in which the unintelligible sentence "Mortuus est Dei filius; credibile est quia ineptum est: et sepultus resurrexit; certum est quia impossibile est" occupied my undivided time, for many weeks of laborious and fruitless investigation.

Thus it will appear that, shaken from its balance only by trivial things, my reason bore resemblance to that ocean-crag spoken of by Ptolemy Hephestion, which steadily resisting the attacks of human violence, and the fiercer fury of the waters and the winds, trembled only to the touch of the flower called Asphodel. And although, to a careless thinker, it might appear a matter beyond doubt, that the fearful alteration produced by her unhappy malady, in the moral condition of Berenice, would afford me many objects for the exercise of that intense and morbid meditation whose nature I have been at some trouble in explaining, yet such was not by any means the case. In the lucid intervals of my infirmity, her calamity indeed gave me pain, and, taking deeply to heart that total wreck of her fair and gentle life, I did not fail to ponder frequently and bitterly upon the wonder-working means by which so strange a revolution had been so suddenly brought to pass. But these reflections partook not of the idiosyncrasy of my disease, and were such as would have occurred, under similar circumstances, to the ordinary mass of mankind. True to its own character, my disorder revelled in the less important but more startling changes wrought in the physical frame of Berenice, and in the singular and most appalling distortion of her personal identity.

During the brightest days of her unparalleled beauty, most surely I had never loved her. In the strange anomaly of my existence, feelings, with me, had never been of the heart, and my passions always were of the mind. Through the grey of the early morning among the trellissed shadows of the forest at noonday, and in the silence of my library at night, she had flitted by my eyes, and I had seen her not as the living and breathing Berenice, but as the Berenice of a dream not as a being of the earth - earthly, but as the abstraction of such a being not as a thing to admire, but to analyze, not as an object of love, but as the theme of the most abstruse although desultory speculation. And now...now I shuddered in her presence, and grew pale at her approach; yet, bitterly lamenting her fallen and desolate condition, I knew that she had loved me long, and, in an evil moment, I spoke to her of marriage.

And at length the period of our nuptials was approaching, when, upon an afternoon in the winter of the year, one of those unseasonably warm, calm, and misty days which are the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon, I sat, and sat, as I thought alone, in the inner apartment of the library. But uplifting my eyes Berenice stood before me.

Was it my own excited imagination or the misty influence of the atmosphere or the uncertain twilight of the chamber or the grey draperies which fell around her figure that caused it to loom up in so unnatural a degree ? I could not tell. Perhaps she had grown taller since her malady. She spoke, however, no word, and I not for worlds could I have uttered a syllable. An icy chill ran through my frame; a sense of insufferable anxiety oppressed me; a consuming curiosity pervaded my soul; and, sinking back upon the chair, I remained for some time breathless, and motionless, and with my eyes rivetted upon her person. Alas! its emaciation was excessive, and not one vestige of the former being lurked in any single line of the contour. My burning glances at length fell upon her face.

The forehead was high, and very pale, and singularly placid; and the once golden hair fell partially over it, and overshadowed the hollow temples with ringlets now black as the raven's ring, and jarring discordantly, in their fantastic character, with the reigning melancholy of the countenance. The eyes were lifeless, and lustreless, and I shrunk involuntarily from their glassy stare to the contemplation of the thin and shrunken lips. They parted: and, in a smile of peculiar meaning, the teeth of the changed Berenice disclosed themselves slowly to my view. Would to God that I had never beheld them, or that, having done so, I had died !

* * *

The shutting of a door disturbed me, and, looking up, I found my cousin had departed from the chamber. But from the disordered chamber of my brain, had not, alas! departed, and would not be driven away, the white and ghastly spectrum of the teeth. Not a speck upon their surface not a shade on their enamel, not a line in their configuration, not an indenture in their edges but what that brief period of her smile had sufficed to brand in upon my memory. I saw them now even more unequivocally than I beheld them then. The teeth ! the teeth ! they were here, and there, and every where, and visibly, and palpably before me, long, narrow, and excessively white, with the pale lips writhing about them, as in the very moment of their first terrible development. Then came the full fury of my monomania, and I struggled in vain against its strange and irresistible influence. In the multiplied objects of the external world I had no thoughts but for the teeth. All other matters and all different interests became absorbed in their single contemplation. They...they alone were present to the mental eye, and they, in their sole individuality, became the essence of my mental life. I held them in every light, I turned them in every attitude. I surveyed their characteristics I dwelt upon their peculiarities I pondered upon their conformation I mused upon the alteration in their nature and shuddered as I assigned to them in imagination a sensitive and sentient power, and even when unassisted by the lips, a capability of moral expression. Of Mad'selle Sall� it has been said, "que tous ses pas etaient des sentiments," and of Berenice I more seriously believed que tous ses dents etaient des id�es.

And the evening closed in upon me thus and then the darkness came, and tarried, and went and the day again dawned and the mists of a second night were now gathering around and still I sat motionless in that solitary room, and still I sat buried in meditation, and still the phantasma of the teeth maintained its terrible ascendancy as, with the most vivid and hideous distinctness, it floated about amid the changing lights and shadows of the chamber. At length there broke forcibly in upon my dreams a wild cry as of horror and dismay; and thereunto, after a pause, succeeded the sound of troubled voices intermingled with many low moanings of sorrow, or of pain. I arose hurriedly from my seat, and, throwing open one of the doors of the library, there stood out in the antechamber a servant maiden, all in tears, and she told me that Berenice was no more. Seized with an epileptic fit she had fallen dead in the early morning, and now, at the closing in of the night, the grave was ready for its tenant, and all the preparations for the burial were completed.

With a heart full of grief, yet reluctantly, and oppressed with awe, I made my way to the bed-chamber of the departed. The room was large, and very dark, and at every step within its gloomy precincts I encountered the paraphernalia of the grave. The coffin, so a menial told me, lay surrounded by the curtains of yonder bed, and in that coffin, he whisperingly assured me, was all that remained of Berenice. Who was it asked me would I not look upon the corpse? I had seen the lips of no one move, yet the question had been demanded, and the echo of the syllables still lingered in the room. It was impossible to refuse; and with a sense of suffocation I dragged myself to the side of the bed. Gently I uplifted the sable draperies of the curtains.

As I let them fall they descended upon my shoulders, and shutting me thus out from the living, enclosed me in the strictest communion with the deceased.

The very atmosphere was redolent of death. The peculiar smell of the coffin sickened me; and I fancied a deleterious odor was already exhaling from the body. I would have given worlds to escape to fly from the pernicious influence of mortality to breathe once again the pure air of the eternal heavens. But I had no longer the power to move my knees tottered beneath me and I remained rooted to the spot, and gazing upon the frightful length of the rigid body as it lay outstretched in the dark coffin without a lid.

God of heaven ! is it possible ? Is it my brain that reels or was it indeed the finger of the enshrouded dead that stirred in the white cerement that bound it ? Frozen with unutterable awe I slowly raised my eyes to the countenance of the corpse. There had been a band around the jaws, but, I know not how, it was broken asunder. The livid lips were wreathed into a species of smile, and, through the enveloping gloom, once again there glared upon me in too palpable reality, the white and glistening, and ghastly teeth of Berenice. I sprang convulsively from the bed, and, uttering no word, rushed forth a maniac from that apartment of triple horror, and mystery, and death.

I found myself again sitting in the library, and again sitting there alone. It seemed that I had newly awakened from a confused and exciting dream. I knew that it was now midnight, and I was well aware that since the setting of the sun Berenice had been interred. But of that dreary period which had intervened I had no positive, at least no definite comprehension. Yet its memory was rife with horror, horror more horrible from being vague, and terror more terrible from ambiguity. It was a fearful page in the record of my existence, written all over with dim, and hideous, and unintelligible recollections. I strived to decypher them, but in vain, while ever and anon, like the spirit of a departed sound, the shrill and piercing shriek of a female voice seemed to be ringing in my ears. I had done a deed, what was it ? And the echoes of the chamber answered me "what was it ?"

On the table beside me burned a lamp, and near it lay a little box of ebony. It was a box of no remarkable character, and I had seen it frequently before, it being the property of the family physician; but how came it there upon my table, and why did I shudder in regarding it ? These were things in no manner to be accounted for, and my eyes at length dropped to the open pages of a book, and to a sentence underscored therein. The words were the singular, but simple words of the poet Ebn Zaiat. "Dicebant mihi sodales si sepulchrum amic� visitarem curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas." Why then, as I perused them, did the hairs of my head erect themselves on end, and the blood of my body congeal within my veins ?

There came a light tap at the library door, and, pale as the tenant of a tomb, a menial entered upon tiptoe. His looks were wild with terror, and he spoke to me in a voice tremulous, husky, and very low. What said he ? some broken sentences I heard. He told of a wild cry heard in the silence of the night of the gathering together of the household of a search in the direction of the sound and then his tones grew thrillingly distinct as he whispered me of a violated grave of a disfigured body discovered upon its margin a body enshrouded, yet still breathing, still palpitating, still alive !

He pointed to my garments they were muddy and clotted with gore. I spoke not, and he took me gently by the hand but it was indented with the impress of human nails. He directed my attention to some object against the wall, I looked at it for some minutes it was a spade. With a shriek I bounded to the table, and grasped the ebony box that lay upon it. But I could not force it open, and in my tremor it slipped from out my hands, and fell heavily, and burst into pieces, and from it, with a rattling sound, there rolled out some instruments of dental surgery, intermingled with many white and glistening substances that were scattered to and fro about the floor.