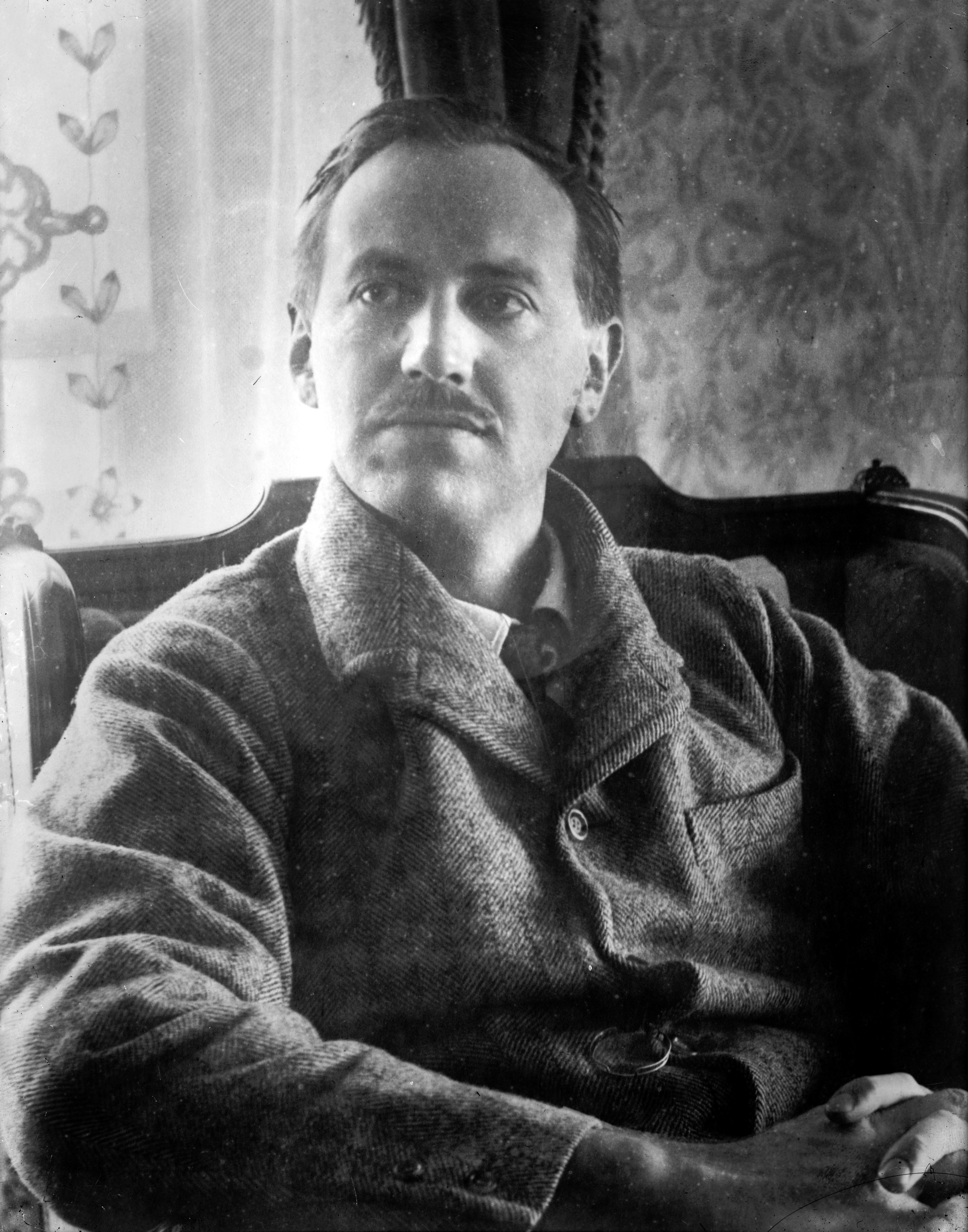

Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany ( 1878 � 1957)

Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany ( 1878 � 1957), was an Anglo-Irish writer and dramatist; his work, mostly in the fantasy genre, was published under the name Lord Dunsany. More than ninety books of his work were published in his lifetime,and both original work and compilations have continued to appear. Dunsany's �uvre includes many hundreds of published short stories, as well as plays, novels and essays. He achieved great fame and success with his early short stories and plays, and during the 1910s was considered one of the greatest living writers of the English-speaking world; he is today best known for his 1924 fantasy novel The King of Elfland's Daughter.

Born and raised in London, to the second-oldest title (created 1439) in the Irish peerage, Dunsany lived much of his life at what may be Ireland's longest-inhabited house, Dunsany Castle near Tara, worked with W. B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, received an honorary doctorate from Trinity College, Dublin, was chess and pistol-shooting champion of Ireland, and travelled and hunted extensively. He died in Dublin after an attack of appendicitis.

On a waste place strewn with bricks in the outskirts of a town twilight was falling. A star or two appeared over the smoke, and distant windows lit mysterious lights. The stillness deepened and the loneliness. Then all the outcast things that are silent by day found voices.

An old cork spoke first. He said: �I grew in Andalusian woods, but never listened to the idle songs of Spain. I only grew strong in the sunlight waiting for my destiny. One day the merchants came and took us all away and carried us all along the shore of the sea, piled high on the backs of donkeys, and in a town by the sea they made me into the shape that I am now. One day they sent me northward to Provence, and there I fulfilled my destiny. For they set me as a guard over the bubbling wine, and I faithfully stood sentinel for twenty years. For the first few years in the bottle that I guarded the wine slept, dreaming of Provence; but as the years went on he grew stronger and stronger, until at last whenever a man went by the wine would put out all his might against me, saying: �Let me go free; let me go free!� And every year his strength increased, and he grew more clamorous when men went by, but never availed to hurl me from my post. But when I had powerfully held him for twenty years they brought him to the banquet and took me from my post, and the wine arose rejoicing and leapt through the veins of men and exalted their souls within them till they stood up in their places and sang Proven�al songs. But me they cast away, me that had been sentinel for twenty years, and was still as strong and staunch as when first I went on guard. Now I am an outcast in a cold northern city, who once have known the Andalusian skies and guarded long ago Proven�al suns that swam in the heart of the rejoicing wine.�

An unstruck match that somebody had dropped spoke next. �I am a child of the sun,� he said, �and an enemy of cities; there is more in my heart than you know of. I am a brother of Etna and Stromboli; I have fires lurking in me that will one day rise up beautiful and strong. We will not go into servitude on any hearth nor work machines for our food, but we will take our own food where we find it on that day when we are strong. There are wonderful children in my heart whose faces shall be more lively than the rainbow; they shall make a compact with the North wind, and he shall lead them forth; all shall be black behind them and black above them, and there shall be nothing beautiful in the world but them; they shall seize upon the earth and it shall be theirs, and nothing shall stop them but our old enemy the sea.�

Then an old broken kettle spoke, and said: �I am the friend of cities. I sit among the slaves upon the hearth, the little flames that have been fed with coal. When the slaves dance behind the iron bars I sit in the middle of the dance and sing and make our masters glad. And I make songs about the comfort of the cat, and about the malice that is towards her in the heart of the dog, and about the crawling of the baby, and about the ease that is in the lord of the house when we brew the good brown tea; and sometimes when the house is very warm and slaves and masters are glad, I rebuke the hostile winds that prowl about the world.�

And then there spoke the piece of an old cord. �I was made in a place of doom, and doomed men made my fibres, working without hope. Therefore there came a grimness into my heart, so that I never let anything go free when once I was set to bind it. Many a thing have I bound relentlessly for months and for years; for I used to come coiling into warehouses where the great boxes lay all open to the air, and one of them would be suddenly closed up, and my fearful strength would be set on him like a curse, and if his timbers groaned when first I seized them, or if they creaked aloud in the lonely night, thinking of woodlands out of which they came, then I only gripped them tighter still, for the poor useless hate is in my soul of those that made me in the place of doom. Yet, for all the things that my prison-clutch has held, the last work that I did was to set something free. I lay idle one night in the gloom on the warehouse floor. Nothing stirred there, and even the spider slept. Towards midnight a great flock of echoes suddenly leapt up from the wooden planks and circled round the roof. A man was coming towards me all alone. And as he came his soul was reproaching him, and I saw that there was a great trouble between the man and his soul, for his soul would not let him be, but went on reproaching him.

�Then the man saw me and said, �This at least will not fail me.� When I heard him say this about me, I determined that whatever he might require of me it should be done to the uttermost. And as I made this determination in my unaltering heart, he picked me up and stood on an empty box that I should have bound on the morrow, and tied one end of me to a dark rafter; and the knot was carelessly tied, because his soul was reproaching him all the while continually and giving him no ease. Then he made the other end of me into a noose, but when the man�s soul saw this it stopped reproaching the man, and cried out to him hurriedly, and besought him to be at peace with it and to do nothing sudden; but the man went on with his work, and put the noose down over his face and underneath his chin, and the soul screamed horribly.

�Then the man kicked the box away with his foot, and the moment he did this I knew that my strength was not great enough to hold him; but I remembered that he had said I would not fail him, and I put all my grim vigour into my fibres and held him by sheer will. Then the soul shouted to me to give way, but I said:

��No; you vexed the man.�

�Then it screamed to me to leave go of the rafter, and already I was slipping, for I only held on to it by a careless knot, but I gripped with my prison grip and said:

��You vexed the man.�

�And very swiftly it said other things to me, but I answered not; and at last the soul that vexed the man that had trusted me flew away and left him at peace. I was never able to bind things any more, for every one of my fibres was worn and wrenched, and even my relentless heart was weakened by the struggle. Very soon afterwards I was thrown out here. I have done my work.�

So they spoke among themselves, but all the while there loomed above them the form of an old rocking-horse complaining bitterly. He said: �I am Blagdaross. Woe is me that I should lie now an outcast among these worthy but little people. Alas! for the days that are gathered, and alas for the Great One that was a master and a soul to me, whose spirit is now shrunken and can never know me again, and no more ride abroad on knightly quests. I was Bucephalus when he was Alexander, and carried him victorious as far as Ind. I encountered dragons with him when he was St. George, I was the horse of Roland fighting for Christendom, and was often Rosinante. I fought in tourneys and went errant upon quests, and met Ulysses and the heroes and the fairies. Or late in the evening, just before the lamps in the nursery were put out, he would suddenly mount me, and we would gallop through Africa. There we would pass by night through tropic forests, and come upon dark rivers sweeping by, all gleaming with the eyes of crocodiles, where the hippopotamus floated down with the stream, and mysterious craft loomed suddenly out of the dark and furtively passed away. And when we had passed through the forest lit by the fireflies we would come to the open plains, and gallop onwards with scarlet flamingoes flying along beside us through the lands of dusky kings, with golden crowns upon their heads and sceptres in their hands, who came running out of their palaces to see us pass. Then I would wheel suddenly, and the dust flew up from my four hoofs as I turned and we galloped home again, and my master was put to bed. And again he would ride abroad on another day till we came to magical fortresses guarded by wizardry and overthrew the dragons at the gate, and ever came back with a princess fairer than the sea.

�But my master began to grow larger in his body and smaller in his soul, and then he rode more seldom upon quests. At last he saw gold and never came again, and I was cast out here among these little people.�

But while the rocking-horse was speaking two boys stole away, unnoticed by their parents, from a house on the edge of the waste place, and were coming across it looking for adventures. One of them carried a broom, and when he saw the rocking-horse he said nothing, but broke off the handle from the broom and thrust it between his braces and his shirt on the left side. Then he mounted the rocking-horse, and drawing forth the broomstick, which was sharp and spiky at the end, said, �Saladin is in this desert with all his paynims, and I am C�ur de Lion.� After a while the other boy said: �Now let me kill Saladin too.� But Blagdaross in his wooden heart, that exulted with thoughts of battle, said: �I am Blagdaross yet !�