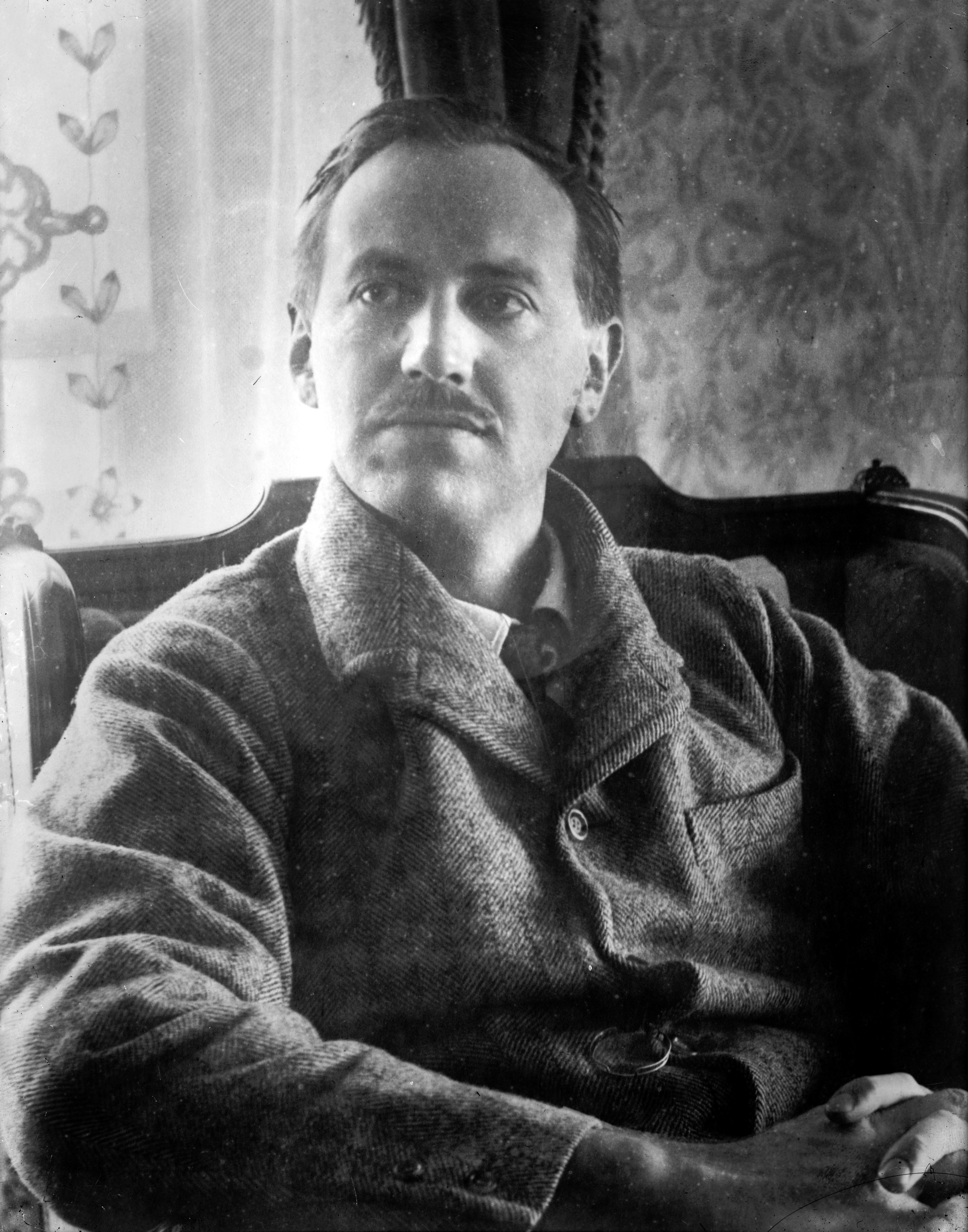

Jean Charles Emmanuel Nodier (April 29, 1780 � January 27, 1844) was an influential French author and librarian who introduced a younger generation of Romanticists to the conte fantastique, gothic literature, and vampire tales. His dream related writings influenced the later works of G�rard de Nerval.

Not far from the highest peak in the Jura, but descending a little down its slope facing west, one could still see, going on for half a century ago, a mass of ruins that had belonged to the church and the convent of Our Lady of the Flowering Thorns. It is at one end of a deep and narrow gorge, much more sheltered to the north, which produces each year, thanks to its favourable aspect, the rarest flowers of that region. Half a league from there, from the opposite end of the gorge, the debris of an ancient manor house is visible which has itself disappeared like the house of God. We only know that it used to be lived in by a family renowned for its feats of arms and that the last of the noble knights to bear its name died in winning back the tomb of Jesus Christ for Christians without an heir to propagate his line. His inconsolable widow would not abandon a place so conducive to the upkeep of her melancholy, but the rumour of her piety spread far and wide as did her works of charity and a glorious tradition has perpetuated her memory for future generations of Christians. The people, who have forgotten all her other names, still call her THE SAINT.

On one of those days when winter, coming to an end, suddenly relaxes its rigour under the influence of a temperate sky, THE SAINT was walking, as usual, down the long driveway leading to her castle, her mind given over to pious meditations. She came in this way to the thorny bushes that still mark its end, and saw, with no little surprise, that one of these shrubs had taken on already all its springtime finery. She hastened to get nearer to it in order to assure herself that this semblance was not produced by a remnant of snow that had failed to melt, and, delighted to see it crowned, in effect, by an innumerable multitude of beautiful little white stars with rays of crimson, she carefully detached a branch to hang it in her oratory before a picture of the Virgin Mary she had held in great reverence since childhood, and went back joyfully to take to her this innocent offering. Whether this modest tribute really pleased the divine mother of Jesus or whether a special pleasure, which it is difficult to define, is reserved for the least outpouring of a tender heart to the object of its affection, never had the soul of the chatelaine been as open to more ineffable emotions than those she felt that mild evening. She promised herself, with a joy that was ingenuous, to go back every day to the bush in bloom in order to daily bring back a fresh garland. We may well believe that she was faithful to that promise.

One day, however, when her care for the poor and sick had kept her busy longer than usual, it was in vain that she hurried to reach her wild flowerbed. Night got there before her, and it is said that she started to regret having let herself be taken over quite so much by this solitary place, when a clarity calm and pure, like that which comes to us with daylight, suddenly showed her all her flowering thorns. She stopped walking for a moment, struck by the thought that this light might emanate from a camp fire made by bandits, for it was impossible to imagine it having been produced by myriads of glow-worms, hatched before their time. The year was not far gone enough for the warm and peaceful nights of summer. Nevertheless, her self-imposed obligation came to mind and gave her courage. She walked lightly, holding her breath, towards the bush with the white flowers, seized in a trembling hand a branch which seemed to fall of itself between her fingers, so little resistance it offered to her, and went back to her manor house without daring to look behind her.

For the whole of the subsequent night, the saintly lady pondered this phenomenon without being able to explain it, and, as she was determined to solve this mystery, no sooner than the following day, at the same time in the evening, she went back to the bushes with a faithful servant and her old personal chaplain. The gentle light shone there as it had the day before, and seemed, as they drew near to it, to grow brighter and more radiant. They stopped then and knelt down, as it seemed to them this light was coming down from heaven. After they had done this, the good priest got up by himself and took a few respectful steps towards the flowering thorns singing a hymn of the church and brushed them aside easily for they opened like a veil. The spectacle that offered itself to their sight at that moment inspired such admiration in them that they stayed for a long time without moving, totally filled with joy and gratitude. It was an image of the Virgin Mary, simply carved in common wood, brought to life by colours given to it by a brush that was rudimentary and wearing clothes that gave a naive idea of luxury, but it was from her that emanated the wondrous splendour that illumined these precincts. "Hail Mary, full of grace," said the chaplain, who had now prostrated himself, at last, and, to judge by the harmonious murmur which promptly arose through all the woods thereabouts after he had uttered these words, one could have thought them taken up by a choir of angels. He then solemnly proceeded to recite those admirable litanies in which faith has, unknowingly, spoken the language of the most elevated poetry, and, following on from new acts of worship, he picked the statue up so as to take it to the castle, where it was to find a sanctuary worthy of it, while the lady and the servant, hands joined together and with heads slightly bowed, slowly came after, merging their prayers with his.

I do not need to say that the wonderful image was placed in an elegant niche, that it was surrounded by odorous candles, bathed in perfumes, laden with a rich crown, and acknowledged, till half way through the night, by the hymns of the faithful. But, in the morning, it could no longer be found and all the Christians who, by gaining her, had been filled with such pure happiness, were much alarmed. What secret sin could have brought down this disgrace on the manor house of THE SAINT? Why had the Virgin Mary left it? What new resting place had she chosen? We may doubtless guess. The blessed mother of Jesus preferred the modest shadow of her favourite bushes to the dazzle of an earthly dwelling. She had gone back, in the midst of the coolness of the woods, to taste the peace of solitude and the sweet exhalations of the flowers. All the people who lived in the castle went there at dusk and found her there, even more resplendent than she had been the previous night. They fell on their knees in respectful silence.

"Potent queen of angels!" said the chatelaine. "This is the abode you prefer. Your will be done."

And indeed, not long afterwards, a shrine embellished by all the adornments that an inspired architect could lavish on it in those centuries of feeling and imagination rose around that venerated image. The great and good of the earth wanted to enrich it with their gifts. Kings endowed it with a tabernacle of pure gold. The fame of Our Lady's miracles spread far and wide throughout the Christian world and summoned to the valley a multitude of pious women who dwelt there according to a monastic rule. The saintly widow, more touched than ever by the light of grace, could not refuse the title of mother superior of this convent. She died there full of days after a life of good works, good examples and sacrifices which rose up like a perfume from the foot of Our Lady's altars.

Such was, according to the handwritten records of the province, the origin of the church and convent of Our Lady of the Flowering Thorns.

Two centuries had passed since the death of THE SAINT, and a young virgin in her extended family was still, according to custom, the sister custodian of the holy tabernacle, which means that she took care of it, and that it was her job to open the tabernacle on feast days when the miraculous image was shown to the faithful. She it was who had the care of maintaining the ever new elegance of Our Lady's ornaments, of removing the dust from them and the harmful insects, of picking, to compose her crown or to adorn her altar, the most gracious flowers in the garden in their growth and the most chaste in their colour, forming chains, garlands and bouquets that attracted in their turn, through the great stained glass window open to the rising sun, a multitude of purple and azure butterflies, aerial flowers indicative of solitude. Among these tributes the flowering thorn was always given preference when in season, and, imitated in lieu of all the others with an art that the good nuns had stolen the secret of from nature, it rested on the breast of the beautiful Madonna as a thick clump knotted with a silver ribbon. The butterflies themselves might have slipped up sometimes, but they did not dare to dwell on these celestial flowers which were not made for them.

The sister custodian at that time was called Beatrix. Eighteen years old at most, she had scarcely been told how pretty she was, for she had entered Our Lady's house when she was only fifteen, as pure and unspoilt as her flowers.

There is a happy or disastrous age at which a young girl's heart understands that it was created to love, and Beatrix had reached it. But this need, initially vague and anxious, had only made her duties more dear to her. Unable to explain then the secret motions that agitated her so much, she had taken them to be the symptoms of a pious fervour which accuses itself of not being ardent enough, and which feels obliged to love enthusiastically and to the point of madness. The unknown object of these loving tendencies eluded her lack of experience, and among the objects that occupied the senses of her ingenuous heart, if we can put it like that, Our Lady alone seemed to her worthy of that deep adoration for which life itself could scarcely suffice. This cult of every passing moment had become the one thing her mind dwelt on, the one thing that charmed her solitude. It filled even her dreams with mysterious languors and ineffable acts of worship. She was often to be seen stretched out in front of the tabernacle, breathing out to her divine patron prayers that were interspersed with sobs, or wetting the space around the altar with her tears, and the celestial Virgin smiled no doubt, from the top of her eternal throne, at that happy and tender mistake on the part of the innocent, for the Holy Virgin loved Beatrix and liked to be loved by her. Besides, she had perhaps discerned in Beatrix's heart that she always would be loved by her.

About that time there occurred an event that raised the veil under which Beatrix's secret had remained so long hidden to herself. A young lord in those parts, having been attacked by murderous footpads, was left in the forest for dead, and, though he had only preserved at most the feeble semblance of a life about to be extinguished, the convent servants transported him to their infirmary. As the daughters of chatelaines at that time were, from their earliest years, in receipt of formulas and recipes with respect to the healing art, Beatrix was sent by her sisters to the bedside of the dying man to help him. She put into practice all she had learned of that useful body of knowledge, but she counted more on the intercession of the miraculous Virgin Mary, and her long and laborious vigils, divided between the cares of a sick nurse and the prayers of a servant of Mary, obtained for her all the success she had hoped for. Raymond re-opened his eyes to the light and, in doing so, recognized his benefactress. He had already seen her occasionally in the very castle she had been born in.

"What's this ?" he cried. "Is it you, Beatrix ? Is it you I loved so much in my childhood years and that the too soon forgotten acknowledgement of that love by your father and mine had permitted me to hope for as a wife ? What grievous twist of fate has let me see you again, chained by the links of a life which is not made for you, and cut off, without any going back, from that brilliant world that you were the principal ornament of ? If you yourself chose this state of solitude and abnegation, Beatrix, I swear to you, you have my word, that it was because you did not yet know your own heart. The commitment that you made in your then ignorance of those feelings that are natural to all that breathes, is null and void before God as it is before men. You have carelessly betrayed your destiny as a wife, as a lover, and as a mother! You condemned yourself, you poor, dear child, to long days of boredom, bitterness, disgust that no pleasure henceforth will be able to assuage the long sadness of! It is however so sweet to love, so sweet to be loved, so sweet to live again through what one loves in the objects that one loves! The pure joys of affection add to life twofold, threefold, fourfold. What tenderness there is in having a friend who worships you, who enhances each moment with ever new causes for pleasure, who only lives to cherish you or please you. The innocent caresses of pretty children, so fresh, gracious, happy to be alive, and that a barbarous whim would then have sent into oblivion! This is what you have lost! This is what you would have lost, Beatrix, if blind obstinacy keeps you in the abyss you have plunged in! No," he continued even more exaltedly, "you will not be ignorant of the plans of your God and mine, who has only brought us back together that we may be forever reunited! You will willingly submit yourself to the vows of a love that begs to enlighten you! You will be Raymond's wife as you are his sister and his beloved! Do not turn away from him your eyes full of tears! Do not pull back your hand that trembles in his! Tell him that you are willing to follow him and never to leave him again !"

Beatrix did not answer. She could not put into words what she felt. She escaped from Raymond's weakened arms and went away troubled, trembling and distraught to fall at the feet of the Virgin, her consolation and her support. She wept as she had previously, but now it was no longer with an aimless and obscure emotion, but with a feeling stronger than piety, stronger than shame, stronger, alas, than that holy Virgin whose aid she called upon in vain, and her tears, this time, were hot and bitter. Many days in a row she was seen, prostrate and a supplicant, and no-one was surprised because all of them in the convent knew of her passionate devotion to Our Lady of the Flowering Thorns. She spent the rest of her time in the sick room of the wounded man whose recovery now no longer depended on assiduous nursing.

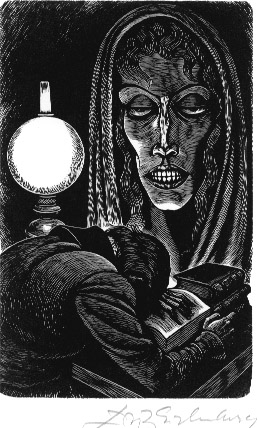

One night when the church was closed, when all the nuns had gone back to their cells, when everything, including prayer, was silent, Beatrix went slowly into the choir stalls, put her lamp down on the altar, opened the door of the tabernacle with a trembling hand, turned away with a shiver, lowering her eyes, as if she were afraid that the queen of the angels would strike her down with a look and threw herself on her knees. She wanted to speak and the words died on her lips or were strangled by her sobs. She drew her veil and her hands to her brow. She tried to compose herself and calm down. She made one final effort. She managed to tear from her heart a few mixed up sounds, without knowing if she was uttering a prayer or a blasphemy.

"Oh celestial benefactress of my youth!" she said. "You that I have so long loved alone, and who will always remain the sovereign of my soul, whatever the unworthy sharing I involve you in! Mary! Heavenly Mary! Why have you forsaken me? Why have you allowed your Beatrix to fall prey to the awful passions of hell? You know I have not given in without a struggle to the passion that devours me! Today the die is cast, Mary, and cast forever! I shall serve you no longer, for I am no longer worthy to serve you. I shall go far away to hide from you the eternal regret my sin fills me with, the eternal bereavement of my innocence which you are unable to restore to me. Let me still now worship you! Have mercy on the tears I shed and which at least prove how remote I have been from the cowardly betrayals of my senses! Welcome the last of my tributes as you have welcomed all the others! If zeal for your altars is worth some gratitude on your part, send death to this wretch who implores you for it before she leaves you !"

Having spoken these words, Beatrix got up, and, with fear and trembling, approached the image of the Holy Virgin. She adorned it with new flowers, seized those that she had just replaced, and, ashamed for the first time in her life of the pious use she made of them that she no longer had the right to, she pressed them to her heart, in a scapular that had been blessed, so as never to part with them. After that she gazed one last time at the tabernacle, cried out in terror and fled.

The following night a coach whisked away at high speed from the convent the handsome wounded knight and a young nun in breach of her vows who accompanied him.

The first year that succeeded this event was almost entirely given over to the exaltation of a love requited. The world itself for Beatrix was a new experience of pleasures that were inexhaustible. Love multiplied around her all the means of seduction able to perpetuate her error and encompass her loss. She only emerged from voluptuous dreams in order to awake amid the joy of banquets, among entertainments devised by strolling players and the concerts of minstrels. Her life was one long crazy feast in which the serious voice of reflexion, stifled by an orgy's clamours, could only have struggled to make itself heard. And yet she had not quite forgotten Mary. More than once, as she prepared to dress, her scapular had opened at the touch of her fingers. More than once she had let drop on the withered posy of the Virgin a gaze and a tear. Prayer had come more than once to her lips, like a hidden flame lurking under ash and embers, but it had been extinguished there by the kisses of her abductor, and, even in her ecstasy, a voice still told her that a prayer might have saved her!

It was not long before she felt the only lasting love is that which is purified by religion, that only the love of Our Lord and Mary gives the lie to the ups and downs of our emotions. Alone among our affections, it seems to grow and get stronger with time, while other loves burn so brightly and are spent so quickly in our hearts of ash. Nevertheless she loved Raymond as much as she could love anyone, but a day came when she saw that Raymond no longer loved her. That day made her foresee the even more atrocious day when she would be quite abandoned by the man for whom she herself had abandoned the honours of the altar, and that dreaded day also came. Beatrix now found herself, alas, with no-one to turn to on earth or in heaven. She sought in vain to console herself with memories and to take refuge in hopes. The flowers in the scapular had withered like those of her happiness. The well spring of her tears and her prayer had dried up. The fate that Beatrix had made for herself had been realised. The unfortunate woman accepted her damnation. The higher the fall on the path to virtue, the more ignominious it is, the more irreparable it is, and Beatrix had fallen from on high. At first her opprobrium frightened her, and then she ended up by getting used to it, the spring in her soul having broken. Fifteen years went by like this, and for fifteen years the guardian angel that baptism had granted to her cradle, the angel with the heart of a brother who had loved her so much, covered his eyes with his wings and wept.

Oh! How many treasures those fleeting years carried away with them! Innocence, modesty, youth, beauty, love, those roses in life that only flower once, and, in addition, conscience that compensates for all other losses! The jewels that had formerly adorned her, the impious tributes that debauchery pays to crime, provided her, for a time, with a resource too apt to dwindle. She was left alone, abandoned, an object of contempt for others as for herself, given over to the insolent disdain of vice, and hateful to virtue, a repellent example of shame and misery that mothers showed their children to turn them away from sin! She wearied of being a burden to pity, of only getting alms that a pious repugnance often nailed to the hands of charity, of only being helped on one side by people whose brows blushed to give her a piece of bread. One day she wrapped herself in her rags, which had been when new luxurious clothes. She decided to ask for her daily bread or a bed for the night from those who had not known her! She flattered herself that she could hide her infamy behind her wretchedness. She set out, the poor beggar, possessing nothing but the flowers that she had formerly taken from the Virgin's bouquet, falling now, one by one, into dust under her dried up lips!

Beatrix was still young, but shame and hunger had left on her brow the imprint of those hideous marks that reveal premature ageing. When her pale and mute face timidly begged help from passers-by, when her white and delicate hand opened jerkily to receive their gifts, there were none who did not feel that her life must have been very different at some stage. Those who were the most indifferent to her halted before her with a harsh look that seemed to say: Oh my daughter! How was it you fell from what you were? And yet her own look could no longer reply to them, for it had been a long time now since she had been able to weep. She walked on and on, on and on: her journey seemed as though it would only ever end with her death. One particular day she had been climbing since sun-up, at a bare mountain's back, a rough and rugged path, without a single house in sight to assuage her weariness. All she had eaten were some flavourless roots torn from cracks in the rocks. Her shoes, worn to shreds, had just come away from her bloodied feet. She felt herself faint with fatigue and need when, night having come, she was all of a sudden struck by the appearance of a long line of lights that were indicative of a large building. Towards these lights she made her way with all the strength left to her, but, at the chime of a silvery bell, the sound of which awoke in her heart a strange and vague memory, all the lights went out at once, and all that now remained around her were silence and night. She nevertheless took a few more steps with outstretched arms, and her trembling hands rested on a closed door. She leaned against it for a moment as if to catch her breath and tried to hold onto it so as not to fall. Her debilitated fingers let her down. They gave way under the weight of her body. "Oh holy Mary!" she cried. "Why did I leave you?" And the unhappy Beatrix passed out on the threshold.

May the wrath of heaven go easy on the guilty! Nights like this expiate a whole lifetime of sin! The keen coolness of the morning had scarcely begun to bring back to life in her a blurred and painful sense of her own identity, when she perceived that she was not alone. A woman knelt at her side was raising her head carefully, and staring at her with anxious curiosity, waiting for her to come round completely.

"God be praised," said the good sister at the convent gate, "for having sent to us so early in the day an act of mercy to perform and a sadness to alleviate! It's a happy omen for the glorious feast of the Holy Virgin that we celebrate today! But how is it, my dear child, that you did not think to pull on the bell or to use the knocker? At no time would your sisters in Jesus Christ not have been ready to receive you. Well, there we are! Don't answer me just yet, you poor lost sheep! Fortify yourself with this beef broth that I warmed up in a hurry as soon as I saw you. Taste this full-bodied wine that will put the heat back in your stomach and help you move your sore limbs again. Let me see that you're better. Drink, drink down all of it, and now, before you get up, if you don't feel strong enough to yet, put this cloak on I've thrown over your shoulders. Put those little, oh so cold hands of yours in mine so that I can restore blood and life to them. Can you feel already the circulation coming back into your fingers as I breathe on them? Oh! You'll soon be yourself again!"

Beatrix, imbued with tender feeling, grasped the hands of the worthy nun, and pressed them several times to her lips.

"I am myself again," she said, "and I feel well enough to go to thank God for the favour he has done me by guiding my steps to this holy house. Only, so that I can include it in my prayers, can you please tell me where I am?"

"And where could you be," the keeper of the gate replied, "if it is not at the convent of Our Lady of the Flowering Thorns, since there is no other monastic building in this wilderness for more than five leagues around."

"Our Lady of the Flowering Thorns!" exclaimed Beatrix with a cry of joy followed immediately by marks of the deepest consternation: "Our Lady of the Flowering Thorns!" she repeated, letting her head fall onto her bosom. "May the Lord have mercy on me!"

"What's this, my daughter?" said the charitable angel of mercy. "Didn't you know? It's true that you seem to come from far away, for I have never seen a lady's clothing that looks like yours. But Our Lady of the Flowering Thorns does not limit her protection to those who live locally. You must know, if you have heard speak of her, that she is good to everyone."

"I know her, and I have served her," answered Beatrix, "but I come from far away, as you say, reverend mother, and you must not wonder that my eyes did not recognize at first this place of peace and blessing. And yet here is the church and the convent, and the thorn bushes where I gathered so many flowers. Even now they still flower! But I was so young when I left them! It was during the time," she continued, lifting her forehead to heaven with that determined look that imparts self-denial to Christian remorse, "it was during the time when Sister Beatrix was the custodian of the holy basilica. Do you remember that time, reverend mother?"

"How could I have forgotten it, my child, since Sister Beatrix has never stopped being the custodian of the holy basilica? She has stayed among us till today, and will remain for a long time, I hope, a subject of edification for the whole community, since, apart from the protection of the Holy Virgin, we know of no surer support under heaven."

"I'm not talking about her," Beatrix broke in, sighing bitterly, "I'm talking about another Beatrix who ended up living a sinful life, and who occupied the same post sixteen years ago."

"God will not punish you for those demented words," said the nun as she drew her to her breast. "The distress and the illness that have affected your mind, have troubled your memory with these sad visions. I have lived in this convent for more than sixteen years, and I have never known anyone in charge of looking after the holy basilica apart from Sister Beatrix. Being as you are determined to perform an act of worship for Our Lady, while I'm making a bed up for you, go, my sister, go to the foot of the tabernacle. You will find Beatrix there already, and you will recognize her easily, for divine goodness has allowed her not to lose in ageing a single one of her youthful graces. I'll come back for you presently and won't leave you then till you're completely well again."

Having spoken these words the keeper of the gate made her way back to the cloister. Beatrix stumbled as far as the steps leading up to the church, knelt down on the approach to them and banged her head against it. Then she grew a little bolder, got up, and, from pillar to pillar, went up to the grille where she once more fell upon her knees. Through the cloud that had darkened her vision she had discerned the sister custodian standing in front of the tabernacle.

Little by little the sister drew nearer to her as she made her daily inspection of the holy place, rekindling the flame in burnt-out candles, or replacing the garlands of the day before with new garlands. Beatrix could not believe her eyes. This sister was herself, not as age, vice and despair had made her, but as she must have been in the innocent days of her youth. Was it an illusion produced by remorse? Was it a divine punishment, a foretaste of those reserved for her by a celestial curse? Racked by doubt, she hid her head in her hands, and rested it motionless against the bars of the grille, stammering from quivering lips the most tender of her prayers from time gone by.

And yet the sister custodian kept on moving. Already the folds of her clothes had brushed against the bars. Beatrix, overcome with emotion, did not dare even to breathe.

"It's you, dear Beatrix," said the sister in a voice for the dulcet tones of which there is no word in any language known to man. "I don't need to see you to know who you are, for I hear your prayers now as I heard them then. I've been waiting for you for a long time, but, as I was sure you would return, I took your place the day you left me, so that no-one would know that you'd gone. You know now what they are, the pleasures and happiness whose picture so seduced you, and you will not go away again. You're here, between ourselves, for the duration and for all eternity. Come back with confidence to the position that you occupied among my daughters. You will find in your cell, the way to which you have not forgotten, the habit that you left there, and you will put on with it your primordial innocence, of which it is the emblem. I owed to your love a grace that was out of the ordinary and which I have obtained for your repentance. Farewell, sister custodian of Mary! Love Mary as she has loved you!"

It was indeed Mary, and when Beatrix, distraught, raised towards her eyes flooded with tears, when she stretched out to her her trembling arms making to her an act of thanksgiving broken by her sobs, she saw the Holy Virgin go up the steps of the altar, re-open the door to the tabernacle, and sit down again there in her heavenly glory under her golden halo and under her festoons of thorn flowers.

Beatrix did not go back down to the choir without emotion. She went back to see her companions whose faith she had betrayed, and who had aged, immune to reproach, in the practice of an austere duty. She slid among her sisters lowering her head, and ready to humble herself at the first shout to announce her fault. Her heart greatly troubled, she lent an attentive ear to their voices, and she heard nothing. As none of them had noticed her departure, none of them paid any heed to her return. She threw herself at the feet of the Holy Virgin, who had never looked so beautiful to her, and who seemed to be smiling. In the dreams of her illusory life, she had grasped nothing that came anywhere near such happiness.

The divine feast of Mary (I think I have already said that this took place on the Feast of the Assumption) was celebrated in a mixture of of contemplation and ecstasy, the finest moments of which far excelled past celebrations of the feastday by this community of virgins, without stain or blemish like their queen. Some had seen miraculous lights emanating from the tabernacle, others had heard songs of angels mixed in with their pious canticles, and had, out of respect, stopped their singing so as not to disturb the celestial harmony. It was said that there had been that day a feast in Paradise as there had been in the convent of the Flowering Thorns, and, due to a phenomenon foreign to that season, all the thorn bushes in the area had burst into flower again so that, outside as well as inside, there were only the scents of spring. It was because a soul had come back to the bosom of the Lord, shorn of all the defects and ignominious shortcomings of our human condition, and there is no feastday in heaven more agreeable to saints there.

Only one thing disturbed for a moment the innocent joy of this flock of virginal doves. A poor woman, sickly and ill, had been sitting in the morning on the threshold of the convent. The nun at the entrance had seen her and had partially relieved her suffering by making up for her a nice warm bed for her to rest her weary limbs in, weakened by privation, and, since then, she had looked for her in vain. This wretched creature had disappeared without a trace, but it was thought that Sister Beatrix might have seen her in the church where she had gone to pray.

"Have no fear, my sisters," said Beatrix, moved to tears by this tender concern on their part. "Have no fear," she went on, as she pressed the gatekeeper sister to her bosom, "I have seen that poor woman and I know what has become of her. She is well, my sisters, she is happy, happier than she deserves, and happier than any of you could have hoped for her to be."

This answer allayed all their fears, but it was noted because it was the first severe word to come from Beatrix's mouth.

After that, the whole of Beatrix's life went by like a single day, like that day in the future that is promised to the Lord's elect, without boredom, without regret, without fear, without any emotions, for sensitive hearts cannot wholly do without them, other than those of piety towards God and charity towards Man. She lived for a century without seeming to have aged, for only the soul's bad passions add years to the body. The life of the good is an eternal youth.

Beatrix died nevertheless, or rather calmly fell asleep in that ephemeral sleep of the tomb that separates time from eternity. The Church honoured her memory by crowning her with a posthumous glory. It made her a saint.

Bzovius, who has examined this story with that solemn critical spirit that canonical writers offer so many examples of, is quite convinced that she was worthy of this honour by reason of the tender fidelity she showed to Our Lady, for it is, he said, purity of love that makes saints, and I would affirm, not with much authority admittedly, but in the sincerity of my mind and heart, that, as long as the school of Luther and Voltaire cannot offer me a more poignant story than hers, I will agree with the opinion expressed by Bzovius.